This blog was co-written by Simon Buckingham Shum and Chris Girdler, and is based on a paper from the AIinHE.org project; read the full paper here

In November 2024, we highlighted some of the key findings from a multi-university survey on Generative AI use, study and wellbeing. When it came to students using GenAI, there was a mix of positive and negative responses, high usage but low trust, and a plea for more guidance and transparency. A follow-up study and survey from the same experts narrows the focus on AI-generated feedback, and asks: how do students use, value and trust this compared to feedback from their teachers?

A matter of trust

The quantitative analysis of 6960 respondents reveals that half of the students surveyed sought feedback from GenAI.

The top reasons for students not using GenAI for feedback related to concerns about the quality of the information and its trustworthiness. A large number of students indicated that they did not use GenAI for feedback because they did not know it was a viable option – but they do use GenAI for other purposes.

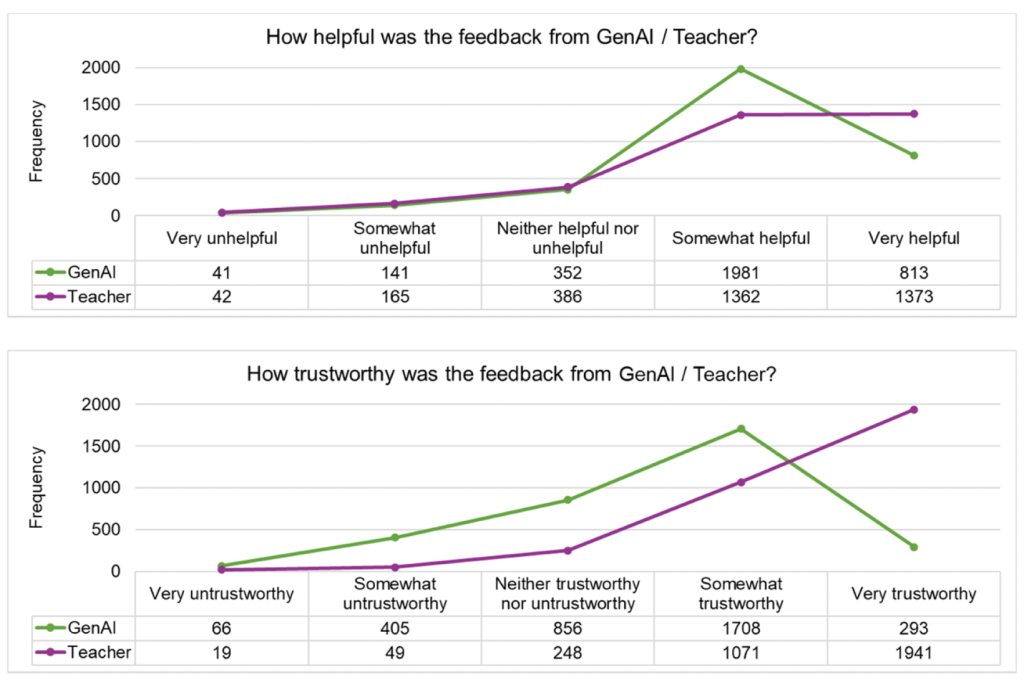

The students who did use GenAI for feedback were asked to compare its feedback to that of their teachers. There was general agreement that both sources were helpful, but teacher feedback ranked considerably higher when it came to trustworthiness (echoing the concerns of those who didn’t use GenAI for feedback).

Pros & cons of GenAI feedback

The study shows that students value the feedback from GenAI because it was less negative in tone, more timely and objective (i.e. less biased), and provides more understandable information. There was also a very strong indication that students felt GenAI provided better access, offering students the ability to get feedback anytime, quickly and in large volumes. A lesser sense of connection was balanced out with this style of feedback giving the perception of a lessened personal risk.

While the students regard teacher feedback as relatively more helpful and trustworthy, their comments suggest that GenAI feedback is not unhelpful nor altogether untrustworthy. There were shared concerns, however, about GenAI’s reliability as well as contextual and disciplinary expertise. GenAI can produce extensively descriptive feedback and summary statements, but teachers are better at identifying the specific issues that needed improving – an academic ability to cut through and identify what really matters.

Room for both

GenAI and teacher feedback appear to serve different needs, making them complementary but not interchangeable. Students can (and do) engage with both, and there are likely benefits from doing so because they can helpfully serve different functions.

Students perceptions of GenAI and teacher feedback can provide important insights into not only how we enact GenAI feedback in institutions but also how we might further understand the value, usefulness and relational impact of teacher feedback practice. The challenge for the sector is to explore how teachers can lean into what they do best: contextualised, expert and challenging advice, in the context of the teacher-learner relationship.

But the AI landscape is moving fast, and here at UTS, as in other universities, we are now deploying pedagogically grounded chatbots — so note the closing caution from the paper:

This survey was completed at a point where very few students would have experienced GenAI feedback explicitly grounded in their curriculum/assignment resources, a development which will likely change as universities provide secure, customised GenAI. This could change students’ perceptions significantly.

Feature illustration by Irina Strelnikova